The Permanent People’s Tribunal (PPT) Session on Agrochemical Transnational Corporations Case Summary

Through victims’ eyes: Crimes by agrochemical TNCs

“I used to mix paraquat with my bare hands because I was not aware of what this would do to me,” said Nagama, an oil palm plantation worker in Malaysia. “The nozzle of the spray tank was clogged, so I tried to open and clean it. But the spray mixture splashed into my eyes… The next morning, my eyes were swollen and I could not see,” said Mardiah, another paraquat sprayer.

“I used to mix paraquat with my bare hands because I was not aware of what this would do to me,” said Nagama, an oil palm plantation worker in Malaysia. “The nozzle of the spray tank was clogged, so I tried to open and clean it. But the spray mixture splashed into my eyes… The next morning, my eyes were swollen and I could not see,” said Mardiah, another paraquat sprayer.

Paraquat is considered as one of the most toxic herbicides introduced in the last 40 years. But it continues to be used in over 100 countries. In Malaysia alone, an estimated 30,000 women are pesticide sprayers, and most have been using paraquat and have been suffering from acute poisoning marked by nosebleeds, skin sores, discoloration and loss of nails, deterioration of muscles and bone, and blindness. Direct ingestion has been known to cause multiple organ failure and death within hours or days. Latest science shows that paraquat exposure is linked to Parkinson’s disease. Grave cases of paraquat poisoning and deaths throughout the years have been recorded in Sri Lanka, Thailand, United Kingdom, U.S., Brazil, Costa Rica, and South Africa.

Paraquat is manufactured by the Swiss corporation Syngenta International AG, which has actively lobbied against measures to ban the herbicide. Syngenta convinced the Malaysian government to rescind the Ministry of Agriculture’s ban on paraquat through pressure tactics and a media blitz which claimed that the pesticide was “safe”. Ironically, paraquat is banned in Switzerland itself, but continues to be used extensively by sprayers in Malaysia and other Third World countries.

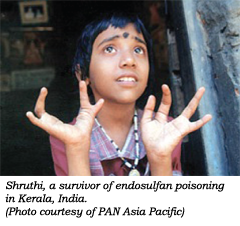

Another toxic pesticide that was widely used in past decades is endosulfan, which is linked to congenital and neurological disorders, birth defects, and delayed puberty. Nowhere are these effects more evident than in the village of Kasargod, Kerala, India, where an estimated 4,000 people have died due to the aerial spraying of endosulfan over cashew nut plantations around the village for more than two decades. Endosulfan passes through the placental barrier, resulting in intergenerational health effects. Many children in Kerala have been born with congenital diseases. One of them is the 18-year old Shruthi. Each hand only has four fingers, and her severely deformed right lower limb was recently amputated. Her mother had been exposed to endosulfan while pregnant with Shruthi, and died of cancer six years ago.

Another toxic pesticide that was widely used in past decades is endosulfan, which is linked to congenital and neurological disorders, birth defects, and delayed puberty. Nowhere are these effects more evident than in the village of Kasargod, Kerala, India, where an estimated 4,000 people have died due to the aerial spraying of endosulfan over cashew nut plantations around the village for more than two decades. Endosulfan passes through the placental barrier, resulting in intergenerational health effects. Many children in Kerala have been born with congenital diseases. One of them is the 18-year old Shruthi. Each hand only has four fingers, and her severely deformed right lower limb was recently amputated. Her mother had been exposed to endosulfan while pregnant with Shruthi, and died of cancer six years ago.

In many countries in South Africa, thousands of cotton farmers have also fallen ill and died due to endosulfan exposure. A survivor, 29- year old Tamou Yaro Orou Boko of Kassakou, Benin, recalled how in 2004, he almost drank endosulfan, thinking it was water. He immediately spewed out the pesticide, but it still caused hot flashes, dizziness, and vomiting of blood even a year after the accident. “The after effects are still present. Today, the slightest smell of chemicals makes me fall into a coma-like state,” he said.

Endosulfan has also been associated with death of bee populations in India, fish kills in Senegal, and cattle deaths in Uruguay. Despite this, endosulfan was only banned worldwide under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) last April 2011. The original manufacturer, German corporation Bayer CropSciences AG, claims that it discontinued endosulfan production in 2007. Nonetheless, it remains unaccountable for decades of poisoning caused by endosulfan, and its other pesticides. Bayer’s earlier banned pesticide methyl parathion, for instance, caused the poisoning of 50 children, of which 24 died, in Tauccamarca, Peru, in 1999 when it was accidentally mixed into their breakfast cereals. The pesticide was packaged in a plastic bag without any indication of its toxic content—only a label written in Spanish that the Quechua speaking farmers could not read.

It is clear that agrochemical TNCs have violated the right to health and life, which includes the right to safe working conditions and the right to a healthy environment. They continue to manufacture and distribute pesticides while knowing of their hazards and risky conditions of use, especially in farms and plantations in the Third World where regulation is most lax.

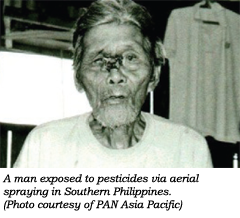

In many countries, chemicals manufactured by agrochemical TNCs ‘trespass’ into homes and communities through aerial spraying and volatilization drift, when pesticides travel through the air as gasses well after applied. Many pesticides drift several kilometers beyond the targeted areas, poisoning people, animals and other crops along the way. In the village of Kamukhaan, Davao del Sur, Philippines, people scurry inside their huts whenever a nearby banana plantation company aerially sprays pesticides—still, they cannot escape the toxic fumes. Many of the villagers have suffered numerous diseases over the years linked to the pesticides sprayed over them on a regular basis. The majority of those killed by pesticides are beneficial organisms and wildlife. Pesticides applied by aerial spraying in New Zealand kill dogs, sheep, cows, horses, deer, wild pigs, bats, and native birds. As a Maori tribe member said, “It is culturally offensive to Maori as the mauri (life force) of wildlife is attacked. Traditional kai (food) also suffers.” Their right to self-determination (the right to freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development) has been violated.

In many countries, chemicals manufactured by agrochemical TNCs ‘trespass’ into homes and communities through aerial spraying and volatilization drift, when pesticides travel through the air as gasses well after applied. Many pesticides drift several kilometers beyond the targeted areas, poisoning people, animals and other crops along the way. In the village of Kamukhaan, Davao del Sur, Philippines, people scurry inside their huts whenever a nearby banana plantation company aerially sprays pesticides—still, they cannot escape the toxic fumes. Many of the villagers have suffered numerous diseases over the years linked to the pesticides sprayed over them on a regular basis. The majority of those killed by pesticides are beneficial organisms and wildlife. Pesticides applied by aerial spraying in New Zealand kill dogs, sheep, cows, horses, deer, wild pigs, bats, and native birds. As a Maori tribe member said, “It is culturally offensive to Maori as the mauri (life force) of wildlife is attacked. Traditional kai (food) also suffers.” Their right to self-determination (the right to freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development) has been violated.

As agrochemical TNCs know very well, certain pesticides have particularly long-lasting effects. Called Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), they persist in the environment, bioaccumulate through the food web, and can

travel long distances over air and in the oceans. The highest concentrations of POPs pesticides have been found among indigenous peoples of the Arctic, and in particular in the nursing milk of mothers. “Our children’s bodies are being contaminated against their will and knowledge,” said Shawna Larson, a resident of Alaska. Their food source, such as marine mammals, also had the highest concentrations of POPs in their bodies. Meanwhile, in Lake Apopka in Florida, U.S., POPs are still found in soil sediments around the lake, even though these pesticides were used and banned decades ago.

The 2008 International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD), participated in by 400 experts from all over the world, stated that the old paradigm of pesticide-reliant agriculture was an outdated concept. The IAASTD concluded that small-scale farming and agro-ecological practices are capable of feeding the world population and provide the way forward. Yet agrochemical TNCs continue to peddle “more of the same” hazardous technologies in the guise of wanting to feed the world.